Building a Performance Fortress

When training in the gym for sports performance, the goal needs to stay the goal. Olympic lifting is a fantastic tool to produce force faster – remembering the aim of becoming more explosive on the field, not learning the sport of Olympic lifting. Greater muscle mass could reduce risk of injury in contact sport, but only if that muscle is well distributed, functional ‘body armour’, and not merely mirror muscles. Chasing a 250kg deadlift is a noble feat, but will it make an athlete better on the court or distract them from their goals? Sometimes perhaps there is such a thing as ‘strong enough’?

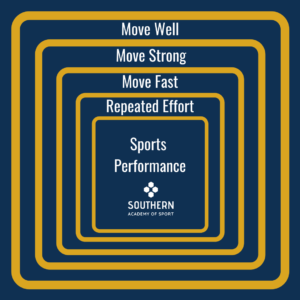

During my seventeen years in the industry I have come to better understand the role of strength and conditioning in a) optimising performance and b) reducing injury risk. I like simplifying complex subjects with visual concepts. I imagine athletic development programs as a fortress. A castle with multiple layers of defence, protecting the crown jewels: staying injury free and at peak athleticism.

The following graphic visualises this idea:

The Moat: Move Well

To quote Mike Boyle, we should never build ‘Strength on Dysfunction’. To me this means seeking to build stability where needed (e.g. the knee) and improve mobility where required (e.g. the thoracic spine). Observing this joint by joint approach, we can assemble a body that moves safely and effectively when it pushes, pulls, jumps, lifts, kicks and throws in sport.

The Outer Wall: Be Strong: Generally, then Specifically.

Strength is both protective against injury and critical for athletic performance. It helps the athlete absorb force, create efficient mechanics and express power – providing we move biomechanically well. Acknowledging its importance, we take a ‘basics first’ approach to strength training.

I was fortunate to assist at the English Institute of Sport during the run up to the London 2012 Olympics. The EIS provide support for athletes of all Olympic sports and often I would find myself helping in gym sessions containing several disciplines of athlete: from swimmers to bobsledders, modern pentathletes to trampolinists.

It would have been hard for an observer to identify which athlete competed in which sport based on their strength programs. They all deadlifted, pulled, pressed, squatted and carried – well. Even at elite level there is a need to be foundationally strong before becoming strong in sports-specific movements. At the Southern Academy of Sport, we have increased several golfers club head speed by 10mph plus, without a single golf related movement – simply through progressing to deadlift 1.5 x bodyweight, performing weighted pull ups and adding 50kgs to split squats.

Only when the athlete hits these types of minimum standards do we train sports specific patterns in the gym. Crucially the most specific exercise for your sport IS your sport – strength work attempting to replicate sports patterns often at best makes no difference, and at worst interrupts those patterns back on the field. If you ride horses, we’re not going to have you riding a barbell around the gym – get on a horse!

The Inner Wall: Move Fast

Sport is performed at high speed. Someone clever may find an example such as Himalayan Free-Dive Bog Snorkelling where movements are slow, but even the ‘sedentary’ sports of snooker and darts include high velocity movements. Some sports may be less obvious, but in many field and court sports the benefit of being the faster athlete is clear to see.

Strength provides the platform to produce the power necessary for sports. Once strong the athlete can focus on performing sport skills explosively. In our gym programs this includes plyometrics, Olympic lifting and medicine ball throws. Our next step is to explore the benefit of bar speed monitors to further relate our work to sports performance.

The Final Defence: Repeated effort.

Moving well, strong and fast will reduce risk of injury and increase performance, for as long as the athlete can maintain moving well, strong and fast.

We ask our athletes a simple question: can they execute in the final minute of the game what they could execute in the first minute? A study on the incidence of injury in professional sevens rugby players found a 60% increase in injury risk during the second half of a match- as starting players tire, and fresh substitutes begin to appear – and a continued increase in risk as multi-day tournaments progressed1. A biomechanically efficient, strong and powerful athlete who tires quickly will risk injury in the later stages of competition and suffer from impaired performance.

Interestingly, coaches often recommend building an ‘endurance base’ before all else. However, before doing so the athlete must requires technique that can be trusted under fatigue, else we risk injury. We only need to consider the commonality of pre-season muscle strains during intense fitness sessions2, or the beginner runner who suffers from knee injuries, to understand the need to move well before high repetition exercise. With reliable technique, it is critical for both injury prevention and optimal performance that the athlete can repeat high velocity sports movements.

The Keep: Sports Performance

Moving well, strong and fast for repeated efforts reduces risk of injury and optimise sports performance.

The problems occur when we neglect one or more of these defences. For example:

- Move well but with low strength levels, the athlete will struggle to produce force when kicking, passing, tackling or punching.

- Being strong without moving well means the athlete is compensating for correct movement, with only so long they can compensate before injury.

- If they move strong through slow movements such as deadlift but can’t accelerate fast, the player will get beaten to the ball.

- Move fast naturally but without moving biomechanically well, and sooner or later injury occurs.

- Fatigue quickly without trusted technique and injury risk increases.

Conclusion

“As to methods there may be a million and then some, but principles are few. The man who grasps principles can successfully select his own methods. The man who tries methods, ignoring principles, is sure to have trouble” Harrington Emerson.

How each line of defence is developed is perhaps less important than understanding that they must be developed, and that each line informs and protects the next.

Though we look to build from the outside in, where the focus on improvement lies depends on the individual athlete – their current status, time of season, injury history, training age, testing and screening data.

Pay attention to moving well, strong and fast, for repeated efforts and the athlete will have built a fortress protecting their sports performance – the key goals of Strength and Conditioning.

References